A Step-By-Step Guide On How To Build The Best New Affordable Housing In America

A Manifesto to change the way we live and build

Allow me to start this piece with a bit of boldness. After all, what’s the point of doing something ambitious if there’s no ambition behind it? Over the next 3 years, I, along with a group of partners, will attempt to build the best new affordable housing in America. Our goal is to create beautiful buildings that are executed to a high quality. We will show that affordable units can be viably built, and once complete, sustainably managed. Should we be successful in our pursuit, we believe this project can serve as a case study for developers, builders, cities, and towns across the country in how to create lovely communities that are attainable to the middle and working classes. Wealth should not be a prerequisite for living in a desirable place.

Why are we doing this? Where do we intend to build it? How, exactly, do we plan on going about it? And most pressingly, have we lost our minds to pursue something so quixotic? On the lines that follow, I will lay out detailed responses to each of these questions, and others that I am sure have been raised by the first paragraph. This is not a utopian dream, but a real project rooted in practical realities. As such, there will be some sections that are quite technical, and others that the reader might find rather dull. Reality is rarely more stirring than fantasy, but in order to reach something approaching an idealized state, we must wade into the banalities of practice.

Before moving on to the first section, an important note: our project won’t fit the conventional understanding of “Affordable” today. Unlike “Capital A” Affordable housing which is reliant on grants and tax credits, ours will be naturally affordable, with rents covering all expenses independently. As you will see in the lines that follow, this distinction is critical. It is not possible to truly build affordable housing if it needs to be heavily subsidized to exist. As far too many people have come to know, when funding dries up in annual budgets, housing is one of the first categories to get cut. We cannot allow our neighbors to live and die by the winds of Washington and the caprice of state budgets. Without further ado, let’s build the best new affordable housing in America.

Why Has Housing Gotten So Unaffordable?

America is in a desperate housing crisis. I’ve written this same line perhaps a dozen times over the last several years, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Depending on what sources one references, the country has a shortage of somewhere between 4 million and 7 million homes. Nationally, the median sales price of a single family home is 5.6 times higher than the median household income—the highest in this ratio’s recorded history. People have to work longer, and spend more than ever before, to be able to buy a home. In the Bay Area, this ratio is more than 11. Half of all renters in America, amounting to 21.6 million households, are burdened by housing costs, spending more than 30% of their gross income on housing. 11.6 million renters are severely burdened, spending more than half of their gross income on housing. These trends have risen linearly over the last decade, and show no signs of reversing.

In looking for answers as to why things have gotten so unaffordable, quite naturally, many have come to believe that profit is to blame. Housing is so expensive, they reason, landlords and developers must be making a killing! Undoubtedly, this is true for some, especially those who have been advantaged by exclusionary zoning policies that have inflated asset values via artificial restriction of new housing supply. While these individuals and firms have profited handsomely, however, their returns have not primarily come from any value they added. Rather, they have been the beneficiaries of rent seeking, a very different sort of profit. Were we to accept this answer, however, simple and incomplete though it is, it would only explain why existing housing has gotten so expensive, not new construction. Or, said another way, rent seeking explains why homeowners and landlords have made a killing, but not builders and developers.

In order to see if developers have done as well, we have to look at the margins they make on their projects. Simply looking at the end price of a home or apartment tells us very little, as the costs of constructing that property may have risen commensurately with, or outpaced, the other input costs. So, have builder and developer profit margins expanded over the last decade? The answer is…it sort of depends. Single family home margins have expanded quite a bit. In 2010, single family home builders reported paltry net profits of 0.5% compared to 7% in 2020, a slight decline from the mid 2010s. But these numbers are a bit misleading. The housing market in 2010 was in dire straights—it had the second fewest existing home sales, and second fewest new home sales, of any year between 1995 and 2023. Before the financial crisis, net margins were 7.3% in 2006. So it seems margins for single family homes have merely returned to recent historical norms.

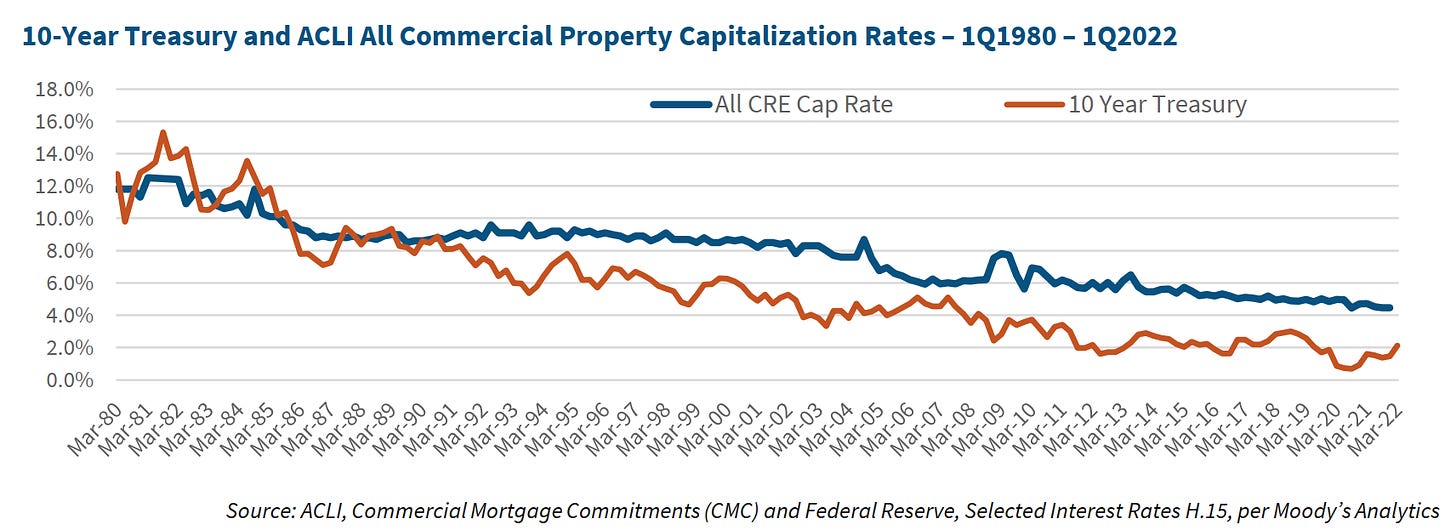

What about apartment units? The best way to gauge margins for rental properties is to look at prevailing cap rates—the rate of return a property can be expected to generate. If a cap rate for a property worth $1,000,000 is 10%, for example, an investor can expect to make $100,000 in net operating income (NOI) per year. It’s important to note that cap rates are not indicative of net margins, as they don’t factor in debt payments. In order to get to a net cash-on-cash return, simply subtract debt from NOI. Interest payments are highly variable from property to property, however, so it’s difficult to know what the true net margin is for the asset class. Some owners may take on a lot of debt at high rates, which can lead to negative annual returns, while others may have very low principal loan balances at low rates, leading to higher free cash flow. Such complexities are not easily reducible and as such one cannot be confident enough to take a position on them. For our purposes, then, we’ll have to make do with cap rates, and understand that true net margins are even lower.

Over the last 40 years, cap rates have compressed in all commercial real asset classes, following declining long-term interest rates and the subsequent yield of the 10-Year Treasury. In plain English, this means higher building valuations, and lower expected operating profit margins. For developers, this means more of their money comes from appreciation, not cash flow or rent.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Our Built Environment to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.