Join Us In Building The Best New Housing In America

An open call to kindred spirits who want to build a better future

This is a shortened version of a longer essay that explores how to build excellent and attainable housing in the current American real estate development environment. In the longer piece, I trace how housing has gotten so expensive, and why current solutions to our national housing crisis are falling short. The essay culminates in a proposal for a paradigm shift in the way we build housing today. This proposal is not an absent theory, but the basis for a real development that I am currently working to build with a group of partners.

For this shorter piece, I have extracted only the relevant sections of the longer essay that pertain to building this specific project, with minimal revisions. If you would like to read the full 13,000 word manifesto, please click here.

Our goal is to build one of the best new housing developments in America. This piece lays out how we plan to do it. If you are interested in being involved, please reach out to me at cobylefko@gmail.com

I hope you enjoy it!

Allow me to start this piece with a bit of boldness. After all, what’s the point of doing something ambitious if there’s no ambition behind it? Over the next 3 years, I, along with a group of partners, will attempt to build the best new affordable housing in America. Our goal is to create beautiful buildings that are executed to a high quality. We will show that affordable units can be viably built, and once complete, sustainably managed. Should we be successful in our pursuit, we believe this project can serve as a case study for developers, builders, cities, and towns across the country in how to create lovely communities that are attainable to the middle and working classes. Wealth should not be a prerequisite for living in a desirable place.

Before beginning the piece, an important note: our project won’t fit the conventional understanding of “Affordable” today. Unlike “Capital A” Affordable housing which is reliant on grants and tax credits, ours will be naturally affordable, with rents covering all expenses independent of subsidy. This distinction is critical. It is not possible to truly build affordable housing if it needs to be heavily subsidized to exist. The longer essay I’ve written on this subject lays out why this is the case. But as this is the shorter piece, I’ll keep it brief. Without further ado, let’s build the best new affordable housing in America.

Where We Plan To Do It

So, where do we plan on building our transformative project? Texas? North Carolina? Florida? Against good reason and common sense, we’re choosing a state that is one of the most difficult places to build in—New York. Specifically Kingston, two hours north of New York City up the Hudson River. Kingston is one of the few places that has gotten serious about housing, having recently overhauled its land use regulations in August of 2023 with the adoption of a new form based code (thanks to terrific work from my friends at Dover Kohl). Among its many triumphs, the new code eliminated parking minimums city-wide, legalized accessory dwelling units (ADUs), and expanded the areas where mixed-use and light industrial buildings can be created.

In the densest part of the transect, where our site is located, there is no maximum floor area ratio, no front or side setback requirements, and we can build out to the full coverage of the lot if we wanted to, so long as no building is larger than 3 and a half stories.

Kingston is eschewing decades of status quo planning in order to solve its most pressing challenges. As of 2022, the city had a vacancy rate of around 1.5%. To put this in perspective, once a city dips below a 5% vacancy rate it is considered to have an emergency level of housing scarcity. Home prices and rents have risen significantly post-Pandemic. With little new supply coming onto the market, had the status quo been maintained, prices would have only gotten more expensive. Astutely, the city recognized that in order to solve its housing crisis, it had to take strong and decisive action.

But we didn’t pick Kingston just because of its new zoning code. Though it makes development a lot easier, it doesn’t make sense to build in a city if people don’t want to live there. And there are many reasons why people are excited about living in Kingston.

Foundationally, Kingston is one the prettiest towns in America. Much of this can be attributed to the fact that it’s very old. The first trading post was set up by the Dutch in 1614, and for the next half century it grew wealthy through commerce with local Native American populations, notably the Esopus Lenape. It received its charter in 1661. A few years later, the British gained control of New Netherland, subsequently renaming the city Kingston. A century later, the city became the first state capital of New York. While it didn’t remain the capital for very long, this heritage is still legible in the city’s fabric.

Kingston grew wealthy from industrialization in the 19th century, benefitting from its location on the river and proximity to New York and ports along the Erie Canal. It reinvested these gains back into its built environment, with many lovely homes, churches, public venues, and parks sprouting up. The good times didn’t last. The advent of railroads and interstate highways diminished the city’s relevance as a hub for transportation. Deindustrialization in the mid 20th century saw an exodus of jobs out of the region. The city fell on hard times.

Fortunately, things have begun to turn around in recent years. Thanks to its proximity to the city, (relatively) cheaper building stock, artistic spirit, and general charm, Kingston has become a haven for creatives and Brooklyn expats. Excellent restaurants, trendy boutiques, and experimental concepts rub shoulders with established institutions. It’s that strange case where the wealth of the 18th and 19th centuries created an excellent urban foundation, but its 20th impoverishment mercifully saved it from the worst of midcentury planning that ravaged more prosperous communities, such that its heritage can be fully appreciated in the 21st century.

The city’s strong leadership, urgent need for housing, enviable location nestled between mountain and river, and creative underpinning make it one of the more compelling places to build in America. Now that we know the place, what do we plan to do?

Our Inspiration, Our Solution

All real estate is driven by capital. As such, if it can be driven by creative developers in a direction that aligns the interests of communities and investors, better outcomes will materialize. This need not be some utopian dream where capital acts as philanthropy or asks limited partners to internalize large losses. Returns can still be generated, but of a fundamentally different character.

Our inspiration for how to generate returns of a different character comes from the 19th century Brooklyn philanthropist Alfred Tredway White. White had long been interested in reducing the plight of the working poor, and viewed housing as the key medium with which to improve their lives; “Well it is to build hospitals for the cure of disease, but better to build homes which will prevent it.”

Recognizing that some profit had to be offered in order to marshal funds for the creation of housing, but not nearly so much as the speculators who were carving up his native borough with subdivisions, White espoused a philosophy of “philanthropy and 5 per cent”. After returning 5% in distributions to investors, all excess cash was either reinvested into the property, spent on events (a 6-piece brass band performed every two weeks throughout the summer at his properties), or given back to the tenants. Tenant distributions were particularly novel, but had a strong logic to them. If renters treated their homes and common areas well, through regular cleaning and supervision, ownership wouldn’t have to spend as much money maintaining them. Less money in operating expenses meant more net income, and the more net income that was generated, the more tenants could make in distributions. Thus there was a direct alignment of interests between ownership and tenants.

Not only were these buildings financed in an innovative way that bolstered affordability, but they were gorgeous, as well. To this day, White’s buildings are some of the most highly desired places to live in New York City. One particularly noteworthy example is Warren Place Mews, a series of 34 row homes built for local families. Overcrowding was the de facto condition in New York’s 19th century slums—not exactly the ideal environment for raising a family. Kids got little light or air, and had nowhere to play. Parents had even less space for themselves. At Warren Place, White sought to rectify this with individual workman’s cottages that could support a growing family. Completed in 1878, they rented for $18 a month, or around $600 at today’s prices.

These rents could be achieved because of the modesty and simplicity of the structures. Yes, labor was far cheaper in the 19th century than today, even after adjusting for inflation. But the rows of homes were identically built, and economized on space, which led to cost savings. Spanning just 11 and a half feet wide, and 32 feet deep, the homes are around 1,000 square feet. Dollars were tactically spent to maximize their impact. A lush and expertly manicured garden runs down the narrow lane which separates the two rows of homes. Though it’s not large, the impact it makes is enormous. Each cottage also had a dedicated yard in the back. Walking through the mews on its slate pathways, it’s easy to see how living in such a dignified, beautiful place would inspire the best out of someone.

Our goal is to apply White’s philosophy to the 21st century, as we believe there are many relevant parallels between the late 19th century and today: Housing needs are existential; Affordability has been deprived of far too many; The status quo of development is leaving many dissatisfied; And those who are least able to deal with our broken system are forced to shoulder the greatest share of the burden. Something has to be done to diverge us from the course we have charted.

For our strategy, returns will be a little bit higher than White’s as the costs of building and maintaining properties has increased in the last 150 years. This rate will not, however, be avaricious. Given that the risk-off rate of return for a 10 year treasury bill is north of 4.5%, a targeted dividend of at least 6.5% seems fair, though this number may be adjusted upwards as we get closer to delivery. This rewards investors for supporting a high-minded project without punishing tenants by seeking to extract as much yield as possible. With a fixed dividend, the expectation of capital can be redirected from a short term flip (which benefits the sponsor as more fees can be charged with a higher velocity of deal flow) to a longer-term hold in alignment with community values, as the proceeds become a stable source of income and investors don’t need to constantly seek out new places to put their money.

This strategy won’t be for everyone, but as of now, it’s hardly an option for anyone in the private real estate markets. While relatively reliable dividends are distributed by publicly traded REITs, these firms deliver a qualitatively different product than the sort of incremental, neighborhood scaled infill that composes our most beloved urban areas, and which we seek to build. REITs have the added pressure of responding to the caprices of the market every 3 months in their quarterly updates. Even the most noble of ideas die on a 10-Q.

Doubtless, there are many wonderful social and affordable projects in Europe, Southeast Asia, and parts of Latin America that we might have chosen to reference. The contexts, however, are too different to be applicable. Unless we change the way housing is financed (as in Europe), exert near-complete control over the market (as in Singapore) or are able to reduce costs through building code revisions and low labor prices (as in Latin America), we will require a distinctly American solution. Anything else is fantasy, or signing up for a years-long march into the abyss. We have deal with the context we have, not the one we’d like to have. Based off of our context, it seems to me that the housing reformer model is the best one available to us today.

What It Will Look Like

Our goal is to create an affordable development of extraordinary beauty that will add much value to Kingston. As has been mentioned, we also hope that it might serve as an inspiration for others to improve their own communities by employing a similar philosophy. If we’re to be successful, however, the design of this project must be worthy of the goals that we seek. While there can be no guarantee of this success, the best way to get close is to work from strong precedent, with talented architects.

There are elements of White’s workman’s cottages that we plan to draw on, namely their intimate human scale, proud yet restrained ornamentation, and embrace of greenery. Their modest size and repetitive form will allow us to realize cost efficiencies.

Most of our inspiration, however, comes from the Low Countries. Specifically, the Godshuizen and Hofjes of The Netherlands and Belgium. These cottage courts are intimate communities that historically served as almshouses for the elderly, the poor, and the infirm. Tenants rarely paid for their lodgings, and when they did, it was a marginal amount. Chapels within the Godshuizen brought communities together for daily or weekly services, and the landscaped courtyards provided areas of respite and communion.

The Godshuis De Meulenaere in Bruges is the paragon of the form. Built in 1613, its 24 homes have housed elderly women in need for more than 4 centuries. As architect Thomas Dougherty has written of De Meulenaere, “The small brick houses block out any noise from the street, and the courtyard offers an almost startling sense of peace, though it is just a few steps from the street.” It is this spirit that we hope to evoke in our own project. Luckily for us, Thomas, who is the North American expert on this form of housing, is serving as our architect for the project.

We’ve chosen these typologies as reference not only because they’re very beautiful, but also because Kingston is a Dutch city. Flemish architecture is, strangely enough, contextual. It is a return to the oldest vernacular in the city. While our project will have some contemporary flourishes, it will find a very comfortable home along the streets of a city that saw much growth in the 17th and 18th centuries.

While we’re still working our way through plans, a preliminary design survey (below) illustrates how the project might look. With efficient floor plans, it’s our hope that much of the effective living space will be directed towards courtyards, allowing for an indoor/outdoor permeability where life is not confined to the four walls denoted in one’s lease.

How We Plan To Do It

In the spirit of transparency and moving the discipline forward, I’m going to lay out precisely how we plan to carry out this project. Far too much of the real estate development process is obscured, which opens itself up to all manner of misunderstanding and conspiracy. This ultimately damages the cause of building better places as people and communities become suspicious of any amount of change, and who may or may not benefit from that change. Clearly describing what we plan to do should discourage misunderstanding, and offer a tangible program people can respond to.

As this project is still in its early phases, I won’t be able to enumerate every cost, nor delineate every line item today, but I hope to paint the broad strokes for where these numbers will ultimately be filled in. And so, here’s how we plan to build the best new affordable housing project in America.

Step One: Acquire Land:

Real estate development cannot be carried out without some patch of land to build on. That makes this first step fairly important. Fortunately for this project, we are in contract for a nearly acre large parcel in uptown Kingston, the heart of the city’s renaissance. It is extremely walkable; the land is only a block away from a large gym, two blocks to the grocery store, and 2-3 blocks away from all of the shops, restaurants, galleries, and cultural amenities of uptown Kingston.

This land will cost $575,000. Our current plans call for 33 units across 18,000 square feet, though the total unit count is subject to change. Presently, our land cost per unit is ~$17,500, which is quite low. The reason we are able to achieve such low costs per unit is due to the city’s permissive zoning, floor are ratio and parking regulations. Unlike other cities that cap the amount of density that can be built on a piece of land directly via maximum buildable square footage, and indirectly via the amount of cars that have to be accommodated, Kingston’s new form based code privileges density. This will allow us to dedicate more of the site towards housing, and less of it towards parking, mechanical, and service space.

Acquiring land for a low basis is a critical step in creating affordable homes. If we were only allowed to build 3 units on the site, each home’s land basis would cost more than $190,000—and that’s before a single shovel moves the first load of dirt. There is no way to keep rents affordable with costs this high.

Step Two: Design, Engineering, Entitlement

Once the land is secured, which we hope to have done in the next two months, we will begin working our way through design, engineering, and then ultimately entitlement.

Design is fairly straightforward. It will start with a preliminary schematic design, where we will work alongside our architects to work out the rough contours of the program. In this phase, we’ll explore the best uses for the site, and map out how we can accommodate them. During schematic, rough floor plans will be laid out, elevations will be drawn, and the plan of the development will start to take shape.

Once we arrive at a place we feel comfortable with, we’ll move on to design development (DD), where key elements of the plan will be finalized. Detailed floor plans, sections, and specifications for finishes will be carried out. During DD, we will lock in how many units there will be on the site, what sort of units they will be, and in what proportions they’ll exist (i.e. 14 one bedrooms, 16 two bedrooms, and 3 retail spaces, etc).

Finally, we will complete the design with a set of construction documents, which will incorporate detailed drawings from a team of consultants and engineers. These drawings will provide specific instructions to our construction team on how to build the project. This is the meat and potatoes of design. A beautiful rendering or plan is all well and good, but if the building is designed without pipes or wires for plumbing and electric, or if it cannot stand upright because there was no structural consultation, the rendering is little more than an artistic expression.

We’re budgeting $225,000 for design and engineering, though of course this number can change depending on where the final design ends up, and how the construction landscape evolves generally.

Once design is complete, we will submit the plans into the city for approval. This stage is known as entitlement. A key reason why we chose Kingston to build our model development is because all of what we wish to accomplish can be done as of right, meaning we don’t need special permission to build it. This is in stark contrast to nearly everywhere else in the United States. For one of several dozen reasons, a Godhuis or Hofje would be illegal to construct in most of the country. Why this is the case is a matter for another time. We know that the quality of what we intend to build will immediately improve the city. It is to the detriment of every other place who decides to uphold the status quo of our woeful development patterns, and prohibit this form of housing. Hoping they may one day find the light is none of our concern. I admire the work of those who labor tirelessly in this fight, but this is not the fight of a developer.

Even in communities where aspirational development is encouraged as of right, entitlement is a tricky process, whose costs are difficult to divine. One never truly knows what a city will require of a developer before a proposal is put in front of them. As such, I don’t feel fully comfortable in sharing our numbers for this phase just yet as I’m not sure how the process will work itself out. Clarity will come in the future. Though this is may be disquieting, development inevitably comes with uncertainty. This is best illustrated in the next step.

Step Three: Construction

Once we have received approvals for our project, we will begin construction. In construction, there is only one certainty; something will go wrong. More likely, many things will go wrong. The job of a developer is to mitigate construction setbacks, and triage issues such that the most pressing ones are dealt with, and the less pressing ones can be lived with.

I don’t know what issues we will encounter, but I’ve set up our construction budget in the hopes of being able to sustain them. Through conversations with local builders and contractors in the mid-Hudson Valley, I’ve learned that new apartment buildings can be delivered from the high $190s per square foot (psf) to the low $200s. Some of these projects have been self-performed, meaning the developer assumes the role of general contractor / construction manager and can realize savings of upwards of 20%. If we assume that a self-performed project costs $200 psf, one with a construction manager, such as we plan to use, should cost around $240. We don’t want to deliver just any project, however. In order to create something that will leave a lasting positive legacy, we’re going to have to spend a little more than traditional developers might. How much more expensive? It’s tough to say. A 10% quality premium, or $24 per square foot, works out to more than $430,000 to play around with. Spread across 33 units, this means an extra $13,000 can be spent on finishes and design. While this isn’t an exorbitant amount of money, it’s enough to make a meaningful difference on a small scale infill project, where dollars can be stretched quite far, and their impact more tangibly felt.

As we know complications will arise throughout construction, I’ve underwritten the model to absorb around 10% in additional costs, setting the final construction budget in the $285 per square foot range.

Developers make money, primarily, from the fees they generate on their projects. We are no different. Where we diverge from traditional developers, however, is in degree. While it’s very common to take an acquisition fee on the purchase price (somewhere in the range of 2%), we will not take one here. Likewise, some developers will charge management fees on the capital they oversee, especially if it’s held in a fund, as opposed to a special purpose vehicle. We will not take an asset management fee, either. We will only take a development fee of 3%, standard for private market rate developers.

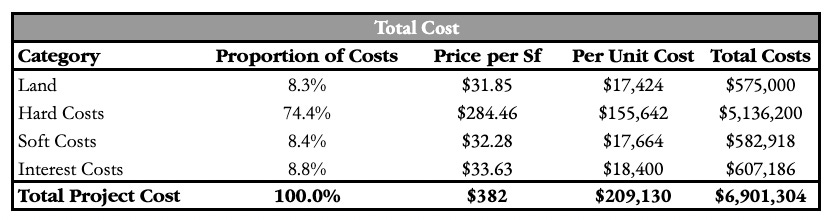

Our total cost structure is estimated as follows. The final result will doubtless vary from these numbers, most likely in interest costs which are difficult to anticipate (one hopes they’ll be lower, though we’re expecting they’ll remain high in our model), and certainly in construction and consultant costs. The point is not to guess the exact costs down to the cent, but to build a budget that is both sufficiently robust enough to absorb the uncertainties of construction without compromising returns.

The lower we can keep costs, the lower we can keep rents. There’s a direct relationship here. So, if we want to keep rents accessible without sacrificing quality, we’re going to have to get creative. This means smaller units, thoughtfully siting the structures on the property, and keeping a diligent eye on the budget, substituting materials where necessary but only doing so when we’re confident it won’t jeopardize the end product. This is not dissimilar to the process of value engineering, but with one key distinction: we plan on holding the property for many years after we build it. Any shoddy construction mistakes will be assumed by us, not some unsuspecting third party. As such, there’s a built in accountability imperative. Any consequences of cheap or stingy decisions made today will be felt by us tomorrow. We can only push the boundaries so far, reconciling cost with rent, before outcomes are diminished for all.

Step Four: Stabilization

We plan to begin pre-leasing the project as we near the end of construction. All of the units will be rented at rates below 100% of Kingston’s AMI. More than half of the homes will rent at rates affordable to households making 80% AMI ($72,000 for a family of 2, and $81,000 for a family of three). Incomes and rents will doubtless change between today and when we deliver the project, but we are underwriting rents based on today’s calculations; $1,476 for a studio, $1,686 for a one bedroom, and $2,026 for a two bedroom. We will maintain pricing flexibility as the project gets closer to completion.

A portion of these homes will be deed restricted to preserve their affordability, though we are unsure how many this will ultimately be. As stated at the beginning of this piece, our goal is to prove that such a project as the one we are endeavoring to build can be managed sustainably upon its completion. This means that we have to mitigate the chance that we lock in rents below what the project can support. We cannot put the ideal of “Affordable” above the reality of those who make their lives in these homes. We cannot act as proper stewards of the project if we set ourselves up for failure where the rents are constrained below what the building costs to operate. While I don’t believe this will be the case for our project, necessary precautions must be taken. A sustainable roadmap for the next decade plus of ownership has to be laid out.

Once the project is fully leased up and stabilized, we will refinance the construction loan into a permanent loan. There are many factors that influence the size of the permanent loan, from the federal funds rate to local market conditions, but regardless of where these variables shake out, we intend to take out no more than we need to in order to pay down the construction loan and its closing costs. The less money we take out at refinance, the lower our stabilized debt payments will be. And the lower our stabilized debt payments are, the more cash flow can be generated, and then reinvested, into the property.

What It Will Take To Get This Done

While it would be great to receive a 3 million dollar grant with no strings attached for our project, this isn’t realistic. If there’s anyone reading this who would like to invalidate this assumption, however, I’d be thrilled to be wrong!

We recognize that we must offer a compelling yield to prospective investors in order to get this project built, and in order to manage it sustainably for a long time. As such, it doesn’t make sense to underwrite to an IRR threshold which can be manipulated by selling the asset quickly, and penalizes the sponsor for holding the investment for a longer period of time. Nor does it make sense to shoot for a certain multiple on investment as it’s nearly impossible to forecast what our property’s valuation will be in 10 years. Instead, we plan to issue a dividend worth around 6.5-7% of an investor’s initial investment. All investors will still maintain a proportionate equity ownership in the property, giving them further equity upside for major capital events, but this is not the driving thesis of the investment. If the value of the property grows in the future, as we have reason to believe, that’d be terrific, but we are not reliant on it in order to deliver the returns we are forecasting.

By positioning the investment in this way, we can align the time horizons of the sponsors (us), investors, and tenants, tying the incentive structure to one of stability and long term stewardship. As we have a pretty good understanding of what our rents, expenses, and interest payments should be for the next few years, we can forecast with some degree of confidence that we can deliver a stable 7% yield to investors—attractive in an environment where the 10-year treasury bill returns less than 5% and has no equity upside.

We want to prove that excellent housing can be built with neither speculation nor significant subsidy as the motivating force of construction. Both have corrupting imperatives we wish to steer clear of.

How You Can Help

We are looking for partners who are philosophically aligned with the vision that has been laid out in this essay. People and institutions who want to be a part of building one of the best new housing developments in the country, and establishing a new standard for real estate development more broadly.

Over the next 3 years, one of the best new housing developments in America will rise in Kingston, New York. We welcome anyone into this adventure with us, in any capacity that they may be interested in signing on for. It will take a village. We are eager to gather the kindred spirits of the nation to make it happen.

For more information, or to ask any questions of this project, please reach out to my personal email at cobylefko@gmail.com.

Onwards in the pursuit of creating a better world. Cras es noster. Let us go forth and make the future in the mold of our dreams!

Beautiful proposal. I appreciate the thought and detail you shared here. I'm envious of your per square foot cost of construction. It's much higher down here in the D.C. area. Not to complexify an already complex process, but have you looked into state incentives for energy efficient construction, appliances, and mechanical equipment? Here in Maryland, we also have an interesting program called C-PACE, where developers can leverage additional funds towards energy efficiency and renewable energy that count as equity, rather than debt. It's a bit complicated and not many banks get it, but can make a big difference in the pro forma. Most states also offer tax credits or other incentives for affordable housing, but I'm sure you're aware of how it works in New York.

Best of luck on your wonderful project. Kingston looks charming.

https://spotifyanchor-web.app.link/e/gffY9i4HrJb