Why Building Better Places Isn’t About Money

Debunking the myth that good design is too expensive

Debunking the myth that good design is too expensive

In popular discourse surrounding real estate development (outside of the narrow realms of Twitter), there seems to be a general acceptance that wherever possible, we should try to create more quality, beautiful places. From local observers, visitors passing through, and casual conversations among friends and family, this sentiment is consistent whenever one is confronted with much of new construction today.

So pervasive is this sentiment, that it’s become a common pastime to guess in futility why we can’t build as we used to. Technology is better, construction practices are more refined, access to materials is far easier than historically was the case, capital is more fluid, and it’s easier than ever to get inspiration on great projects from around the world. Is it just too expensive to build like we used to? What gives?

Common Suspects

In searching for answers, we arrive at a few common suspects, all of whom share some blame, but not enough to explain the grinding down of our places to the dismal state they exist in today. There’s our usual foe, modern zoning codes, which demand many things of buildings. From intensity, to setbacks, bulk, lot size coverage, parking minimums & height provisions, our buildings aren’t shaped by the hands of talented designers, but the sterilized, pseudo-technocratic regulations that guide how structures must interact with the built environment. In some studies, parking minimums have been found to account for an average of $50,000 in increased project costs per space, and upwards of 50% of the rent of new apartments. It’s not a matter of necessity, but antiquated code that forces an arbitrary amount of parking and costs.

More broadly, the guiding principles of road design within planning disciplines mandate harsh expanses of asphalt that stretch out & widen our cities beyond human scale, and endanger our communities. Wide roads are anathema to good places. They’re also very expensive to maintain.

New buildings are governed by building codes, those essential provisions that designate best-practices of creating safe, secure, habitable places. These codes shape design by laying the framework for how structures can safely rise through a checklist of items. While this shouldn’t theoretically impact design, as the integrity of a structure can be ensured through a near limitless variety of forms, some of these codes are needlessly prescriptive, which leads many builders to revert to the lowest common denominator. For new apartment buildings, these are known as 5-over-1s. They’ve become the most commonly built structures due to their ease of conducting the economies of scale required by their sponsors, while passing the minimum thresholds of the IBC. Through sheer efficiency, baseline adherence to building codes, and little consideration of design, these utilitarian boxes have been copy and pasted around the country, often masquerading as “luxury” structures.

Developer greed may play a part in our scarcity of good places, but I believe it’s marginal. Value engineering, the process of cutting back embellishments in a construction project to the bare minimum, is often blamed for the banality of contemporary design. But it occurs later in the development process, after plans have already been submitted. Value engineering takes plans that were already bad, and makes them worse. Besides, there’s a pretty direct correlation between the quality/beauty of a place, and the returns it yields. If developers were so greedy, they’d be building the most audacious places in search for the highest yield. Instead, they opt for a lesser route.

A systemic disease

The main reason why our places are less beautiful than they used to be, as I see it, is much less satisfying an answer than any of our common suspects present on their own. It’s an underlying ethos that courses through modern building practices. It’s not greed. It’s a systemic laziness, lack of thoughtfulness (or, lack of creativity), and perhaps no small degree of fatalism. When combined with our common suspects, these factors come together to limit the potential of our places before costs are even factored into the equation. Combatting them isn’t a matter of spending more money, but rethinking (and thinking, generally) about how our places should be shaped.

Perhaps the most important driver of this disease of thoughtlessness is who’s building our places today. Whereas in the past, our communities were spearheaded by craftsmen, designers, and developer entrepreneurs who both valued creating solid, quality places in their backyards, and had the freedom to do so, that’s not the case today. Most new building is subject to antiquated zoning codes that are carried out by institutionally backed developers who care little of the street-level impact their projects have. These firms tend to be out of towners who have little stake or vested interest in the neighborhoods they build in beyond their stabilization cycle. So long as the economics work, and the units are occupied, the project is deemed successful. Any qualitative impact it may potentially have is deemed superfluous, or not considered at all.

I don’t say this in jest or animosity. This isn’t an anti-capitalist, or anti-public sector take. Large companies with sufficient capital are needed to help us build out of our desperate housing crisis. But the honest truth is that these aren’t the best place makers we have. Those overseeing development in the public realm are often hamstrung by decades of codified rigidity turned status quo that limits their ability to be good shepherds of land use.

While economies of scale are partly to blame for yielding the uninspired structures that dot our landscape, mass produced housing can still be of exceptional design (both urban & architectural) quality. Brownstone Brooklyn is little more than the copy and pasted results of developers building housing in the then suburbs. And yet they’re exceptional. The issue comes from those who direct the design, and the limitations imposed on them. While architects may conceive a vision for a project, developers drive the process, setting forth the vision of what a building should be, based on the ground rules of zoning. Architects, as they’ll be loathed to tell you, are contractors subject to their client’s desires. If a developer doesn’t agitate for better design, or more often explicitly expresses a need for efficiency without embellishment, the lowest common denominator reigns supreme. This has become the default.

This is because the kind of people who are interested in creating thoughtful, beautifully designed places don’t typically find themselves in the rooms where the vast majority of our places are created. These folks don’t operate in many-screened bullpens wearing formal workwear (or increasingly, and ever-so generously allowed by these institutions, business casual), guiding institutionally scaled development. That tends to be the purview of number crunching efficiency hawks, who don’t think much of the qualitative aspects of real estate development beyond whether a building should have a gym, rooftop deck, or “game room”. Very little consideration is given to how buildings meet the street, and interact with their neighborhoods.

The *shrugging shoulders, temporarily raising palms upwards, pursing lips downward, and errant escape of “eh” from one’s vocal cords* that accompanies design decisions at institutional firms doesn’t leave much room for thoughtfulness. If one is modeling deals sitting in New York or Chicago, the impact their keyboard strokes might have on Tampa or Boise are both unknown, and unconsidered. In short, the people driving development are agnostic of the impact their designs have on communities.

What’s most distressing, however, aren’t the operating imperatives that fuel institutional development, but how simple it is to create good places. We have scores of fantastic historical precedent all around us, and ever more contemporary development worthy of celebration. In the past, it’s not as though the builders of our most beloved neighborhoods in the US (Cobble Hill, Georgetown/Capitol Hill DC, Center City Philly, Back Bay Boston, etc.) were genius designers who studied at the alters of Palladio, Brunelleschi, Vitruvius, or da Vinci. They copied much of their work, referencing common pattern books that laid out rules for building structures with high integrity, but were relatively simply to stand up. They weren’t structurally impeded from building, so they built. Today, we don’t prioritize good design, and make it harder to do for those that want to, despite its many consequences.

Foundation of Good Design

Good design is a basic matter of a sufficiently enabling foundation, and thoughtfulness. It doesn’t take much — just a consideration of how people perceive space and actually interact with the built environment, enabled by looser zoning and planning. To think of people not as abstract names on a rent roll, or receipts at a coffee shop, but as living, complex beings with many and varied motivations. It’s a matter believing that it’s possible to do better.

While design is subjective, attractive places are not. It goes well beyond cost. As humans, we’re hardwired to be attracted to certain elements in the built environment. Without diving too deep (if you want to take a deeper look, read more here), we’ve evolved to embrace certain places, and reject others, based on sub-conscious psychological responses. Put more simply, our brains signal to us what places we should perceive as attractive or not based on a variety of elements we’re conditioned to gravitate towards, or repel from. Wide, sharp, open places are bad because they leave us vulnerable to danger, while intimate, symmetrical, ornamental, and properly scaled places with natural materials make us feel protected and stimulated. As a species, our brains inform us of what places are likely to be good or bad for us. That’s part of the reason why there aren’t many people in the world who could deny Venice’s beauty. This is an objectively psychologically attractive place.

The foundation for attractive places starts well before any building is conceived. While this is outside of a developer’s purview, it’s firmly within the planning department’s — who are themselves not immune to a lack of thoughtfulness, laziness, or fatalism. In order to create places that are attractive, there are a few important foundational elements.

Beauty starts with streets; they must be designed for people first. Cars must defer to all other road users. The right of way, which includes all the public space between property boundaries across a street like sidewalks, streets, and trees, is one of the most important components of beautiful places. An open street sparsely lined with buildings can make us feel small and exposed. It also leads to cars going faster, whose danger validates our brains perception of open streets being dangerous. A narrow road with fewer structures can still make us feel cozy, and protected. If you want narrower streets, talk to your transportation engineer (and come armed with Confessions of Recovering Engineer). But narrow streets are only as good as the scale of the buildings that front them. As roads narrow, buildings cannot get too tall as they’ll restrict light from the street. But too small, and they won’t be able to satisfy the needs of a place (including housing, offices, retail, community services, etc). Getting this balance right is critical.

It’s important to bring buildings up to the streets, so people can interact with them. In most communities, set back regulations mandate how far a building must be from the street, for no real reason other than preserving an often unused, and woefully unsustainable front yard. When we set buildings back, we antagonize our neighbors, and anonymize space. The final bit of foundation I’ll touch on is the need for mixed-use. Beautiful places are vibrant places. In order to ensure vibrancy, there must be reasons to be somewhere at various hours of the day, not just when one sleeps, when goes to work, or when one wants entertainment. Mono-use neighborhoods breed boredom.

These are all very simple, obvious things even, for those who study it. We can’t let planners and engineers off the hook for continuing to rubber stamp foundationally horrid places in the name of laziness, or a futility that it won’t do anything. All it requires is for one to think a little more deeply about what exactly makes for a good place. One trip to a city or town with the right foundational elements is all it takes to get the ball rolling. Remember, copying is encouraged here! This is the least we can ask of those who set the framework for our places.

You might counter in opposition to this advocacy for better designed places that it’s not just a matter of desire or foundations, but of cost. Yeah, it would be great if we could build better places, but we can’t don’t do that here. Besides, it will just be expensive and luxury, and there’s no way to change that. It’s worthless to create better places if they’ll only be reserved for the wealthiest among us.

The best part is that enabling good foundations isn’t expensive at all. It may require some legal & branding fees, and additional computing power, but it’s primarily an intellectual exercise. Changing codes and planning documents is solely a matter of reimagining what’s possible. Many of these proposed interventions — like reducing parking minimums and narrowing roads — could save money, and yield safer places. Creating a better foundation means there’s far less asphalt involved, fewer miles of sewage, water, and electricity lines to build and maintain, and perhaps most importantly for longevity (which is what foundations should be concerned with), places that can support themselves with their own tax dollars. The potential environmental, societal mental & physical health, and economic gains are considerable.

Tokyo is perhaps an illustrative example of the power of good foundation. By most accounts, Tokyo is a very attractive place. But those accounts would also not describe the city’s architecture as exceptional. It may very well be declared poor, or at the very least perfectly unremarkable. But because of elements like the city’s narrow streets, vibrant mixed-use nature, strong walkability, intimate built scale, and fine grained composition, it’s one of the most beloved places in the world. What’s more, because of the city’s zoning (which is pre-empted federally — a massive benefit!), it’s much easier to add new housing where it’s most needed, at an efficient, and relatively quick pace. This has kept Tokyo one of the most affordable major cities in the world. For a deeper look into how Tokyo has remained affordable, I highly recommend listening to the UCLA Housing Voice Episode with Jiro Yoshida.

No, building better doesn’t cost more money. We must think critically about how to make all of our places better, so that everyone can be inspired by the world around them, not just a group of one’s ideologically imposed subject choosing. This just requires a change in thinking, an understanding of where costs really come from in development, and the ability to get creative with an excel model. Let’s do the math.

Doing the math on good design

With a good foundation, we can create excellent places in the built environment at reasonable costs. To prove this, I’ll show the numbers on two projects I have some data on. One is utterly simple — a great piece of urban fabric that provides for essential community needs. The other is pure luxury. I’ll try to keep it at a high level for those who are number-phobic!

First, to Portland, Oregon. Jolene’s First Cousin is a mixed use apartment building in the city’s Creston — Kenilworth neighborhood. The vision of Kevin Cavanaugh (through his firm Guerrilla Development), and architect Brett Schultz, the project features 13 apartments and 3 retail units. 11 of the apartments are SROs for formerly homeless individuals. This is real estate with a profound social impact, and tangible community benefit. While it could hardly be mistaken for a regal palace, it’s quite a lovely little project. Situated on a corner lot, the colorful siding (made of wood or fiber cement panels) is punctuated by large glass openings, which make it a contextual, welcoming neighbor. The retail spaces make it a community asset.

The total cost for the project was $2.2 million, $1.62m excluding land costs. On a per square foot basis, this is a very reasonable $359, and just $171 psf in construction costs. To put these numbers into perspective, all in, each unit cost just $137,500. Though the units are SROs, making a direct comparison tenuous, where else in a major city would one be able to build a new home for $137,500? The apartments rent for just $425 each.

Make no mistake, this project took work to deliver the results that it did. Cavanaugh had to get creative with how he financed the project, planned it, and found partners to occupy it. He had to employ an incredible degree of thoughtfulness. It would have been far easier to ignore the social needs of the community, and deliver an uninspired box. Instead, he bucked the status quo and the neighborhood was graced with charming buildings that meaningfully support those in need, and benefit the community as a whole.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have $4m luxury townhomes in New York. Before you get your pitchforks out — let me explain!

Fairfax & Sammons designed the 8 townhomes above in Downtown Brooklyn, which were developed by Strategic Development and Construction Corp IBEC. A quote from architect Richard Sammons proves insightful:

“The red brick-on-block facades, trimmed with brownstone cast stone and sheet-metal cornices, reflect Brooklyn’s rich architectural heritage. “Unbelievably, this project was done for under $300 per square foot,” Sammons says, adding that the units sold quickly. ‘It proves that good design can be done on a low budget; the only cost is brain power.’”

The sub-$300 psf Sammons refers to are the development costs, which aren’t considerably higher than the $245 psf in development costs at Jolene’s first cousin. At first blush, this is a bit shocking. What explains the difference between a $425 rental and a $4m townhome? Part of the reason is the size of these homes. They’re big, ranging from 3,400 to 3,800 sf. On the larger end, the development costs are just over $1.1 million — no small sum. But of much greater cost is the land is here. Over two transactions secured by a larger mortgage, the costs of land for this project were $8,450,000 (Brooklyn block number 171, and lot number 101, for those wanting to see the records). At ~9,500 sf, or less than a quarter of an acre, the land cost nearly $900 psf! That’s an extraordinary amount, more than 3x the cost of the design!

With 17,913 square feet built, the total development cost is ~$5.3M. With land and holding fees considered, this project likely cost $14,000,000. Spread across 8 homes, this averages out to $1,750,000 per unit — not exactly cheap. But if we strip out land cost for a second, the units would only cost ~$660,000 per door — much more reasonable, but still pricey. Let’s go a layer deeper. If these homes had the same form, but were broken up to allow for smaller, discrete units on each floor (750 is a perfectly reasonable size for a one bedroom apartment, and maybe 1,000 sf for a two bedroom) of equal mix, we’d have 10 one bedrooms & 10 two bedrooms, with some space left over. Now, the total costs of construction would be ~$265,000 per unit. Of course, we can’t strip away land cost, but it’s illustrative in proving that exceptional quality of design isn’t the driving force in price. If this is true for some of the highest quality townhomes built in the the last century, what can merely very good homes cost?

It must be mentioned that these projects, as with every other real estate, are bound to the constraints of targeted returns required from Limited Partners. Not all projects can be as noble or uniquely financed as Jolene’s First Cousin, but Guerrilla did the work to find a capital stack that could support their vision. The considerations made by Guerilla and Fairfax & Sammons on behalf of their client are above and beyond 99% of what’s built today. But they needn’t be. They didn’t even have to get zoning variances!

Unlock better places, Lower land costs, embrace optimism.

Good design, whether simple or exceptional, is not the reason why our places have gotten more expensive. In fact, a great deal of design that’s fundamentally attractive doesn’t really cost that much more money. Most luxury design embellishments are superfluous, the built equivalent of a $2,000 gold leaf, caviar topped pizza. Sure, marble, masterful craftsmanship, and stone gargoyles are great, but we don’t need them to have excellently designed places. Okay, maybe a few gargoyles. These finishes exist in maybe a handful of homes nationally, — not nearly enough to be used as an argument against the importance of design. And yet it persists out of ignorance.

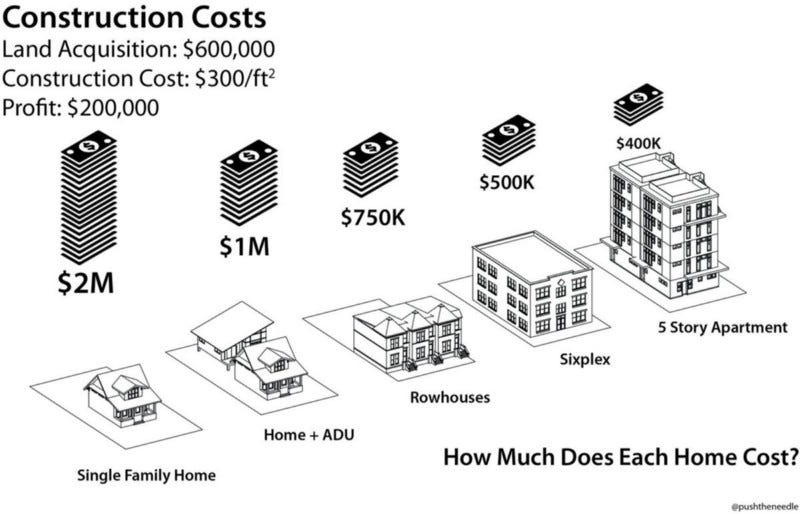

The key determinant to a home’s cost is the land. Go look at the assessments for homes in wealthy communities or unaffordable cities. The land is almost always worth more than the improvements, and significantly so. High land costs are a function of high demand that’s not being properly addressed. Often the value is artificially inflated through a suppression of zoning (like a limited edition print). While the land price won’t get cheaper if one were able to add more units to a lot, the relative cost of the homes would. If only one home is allowed on a $10,000,000 lot, the relative land basis is $10,000,000. But if 50 homes are allowed on that lot, the relative land basis is $200,000. This matters! It’s incumbent upon planners to allow for the intensity demanded by the market to be met, not preserve the high relative cost of land for the most elite classes. This has led to the downfall of places like San Francisco.

Creating good and affordable places requires the cooperation of planners and developers. Planners must lay out the right foundation for places, and be responsive to the demand of a market. Developers, for their part, must give a damn about the communities they’re building! This, admittedly, is tough to legislate, but we need not be so prescriptive. In city after city, neighborhood after neighborhood, the most expensive places are those with the best design. If we simply allow for more buildings to be built in places with the right foundations, the development will follow. The price of good design would drop since it wouldn’t be so scarce, allowing more people to experience it. In enabling this, developers will be rewarded for building the right way.

Under this new foundational paradigm, there’s no excuse for developers who build subdivisions on cheap land to not deliver attractive projects. The most expensive part of the project is effectively mitigated. If a development is still a homogenous morass of sprawling lots, wide roads, and poor design, it cannot be dismissed as one’s “preference”, but rather a laziness subjected upon those who are looking for reasonably priced housing and space, but end up dependent on cars, with poor health and community outcomes.

Building beautiful places isn’t about the cost. With the right foundation, and the proper amount of thoughtfulness that creating the spaces where people spend the entirety of their lives requires, our communities can become sublime oases; the kind of places we take vacations to, or admire on social media. Not only will we be creating more beautiful and livable places, but we’ll reap incredible municipal savings and community rewards for the trouble. Through responsive planning, and thoughtful development, we can create a better world for tomorrow.