New York City is an expensive place to live. This much is obvious. But in the last 6 months as the city has emerged from the doldrums of Covid-19, this feels especially true.

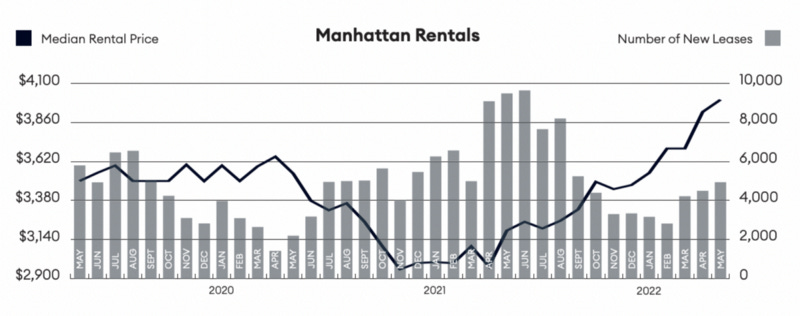

While there was a brief period between May of 2020 through the fall of 2021 where rents remained below previous highs, the time for deals is now long gone. In February of this year, the median rent for apartments in Manhattan eclipsed the pre-Covid peak of $3,650 in April of 2020, and it’s only continued climbing. In May, median rent broke $4,000 a month for the first time in the borough’s history. Average rent hovered at $5,000.

It hasn’t been much better city wide. Medians rents in Brooklyn as of May were $3,250, and nearly $3,000 in Northwest Queens. Average rents, and apartments with more than one bedroom, were much more expensive.

These extraordinary prices have led to some equally extraordinary scenes. Lines of dozens of people queuing up to tour (small and costly) apartments prevail. Overcrowding has become a condition of life. Nearly 10% of all households have more than one person per room, though actual numbers are likely much higher, as immigrants in far off neighborhoods living surreptitiously in basements go unrecorded. Roommates are required.

As a New Yorker who works in real estate (though not in New York real estate), I get a lot of questions about the market. Why is New York’s rent so expensive? Are landlords just greedy? Is there a bubble? Will rents come down soon? As someone who has unsuccessfully been trying to move back into the city for more than a year, I’ve been looking for answers myself. Though apartment salvation doesn’t seem likely in the near-term future for me, luckily, the answer to most of these questions is more easily realized.

So, what’s going on in New York?

We’re not building enough housing

Walk most streets in lower Manhattan after 6 or 7 o’clock in the evening, and you’ll be immersed in a raucous celebration of urban life. After years cooped up inside, deprived of social contact or physical connection, people have flooded into New York to experience perhaps the most dynamic embodied social scene in the world.

Many have identified this rush back into the city as the cause for skyrocketing rents. The competition being so fierce, the logic follows, people are willing to spend whatever they have to in order to take part in the dynamism of the city right now, which feels special in a historic, era defining way, despite broader macroeconomic concerns. While this is no doubt true, it’s only part of the story. In a city as large as New York, with an economy and housing market as mature as the city’s is, why should an uptick in desire over a few months lead to price shocks of this severity occurring so quickly? Moreover, why do people have to spend as much as they do in order to experience the city? Our best urban areas should not be the cloistered domains of the wealthy or well connected, but bastions of opportunity for all who heed the call.

Indeed, that call has rung loud in the last decade. From 2008 to 2018, the city added 675,000 jobs, furthering its position as the one of the world’s top labor markets. Though New York hasn’t fully recovered its pre-Covid employment base, with the rise of remote workers moving into the city and replacing many daily commuters from the suburbs, the compounding impacts of agglomeration will soon see that base be fully recovered. In a vacuum, this would be great news for any place. But not somewhere that’s failed to make the necessary provisions to welcome those jobs.

From 2010 to 2020, the city only added 206,000 net units of housing. To put this into perspective, New York City added 3.25x the number of jobs as new housing units. That’s 3.25 additional people who jobs have been created for, fighting for each singular unit of housing. But that’s only true in a vacuum; if each unit of new housing was expressly dedicated to someone who took one of those 675k jobs. In reality, there’s even more pressure than just a 3.25x imbalance. We’ve not only significantly under built places to live for who move tot the city for those jobs, but those who would aspire to move to New York without a job, whether to go to school, follow their professional dreams on a whim, or just get the chance to live in this most profound collection of boroughs.

This sort of poor governance is chronically destructive. It not only sends a message that a place can’t do the simple things right, but that it has poor prospects for the future, as it will turn away those who come seeking opportunity. Instead of making their livelihood in New York, those would be residents will move elsewhere, delivering to that city their unique talents, culture, presence and economic contributions. While this will doubtless deprive New York of its next generation of artists, visionaries, builders, and thinkers who deliver invaluable cultural clout and global goodwill, more importantly, it will deter the everyday people who make a city run. They’ll move to cheaper housing, as amenities do little good if one can’t afford them.

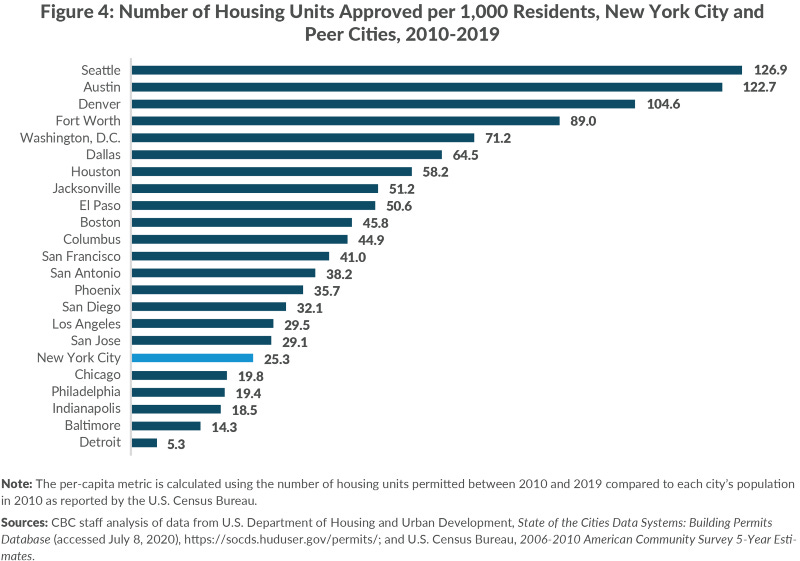

It’s not as though New York is some rising urban star, ill-equipped to meet an unexpected deluge of new residents, scrambling to build appropriate infrastructure. Far from it. Besides, those rising urban stars of the moment have proven more capable of rising to the challenge of welcoming new residents. Cities, like Austin, Denver, or even Columbus, have built considerably more housing per capita than New York in the last decade. All are far more affordable than New York as a result.

What’s troubling is this trend isn’t new. The high prices of today are the result of decades of mismanaged policy. Though one might associate the cranes and construction sheds endemic to the city as indicative of much housing being created, it’s illusory, and has not been nearly enough. Despite growing by more than a million people since 1960, the city has failed to permit anywhere close to the amount of housing it was authorizing in the early sixties. An outlier in the amount of permits issued in 2015 — the result of a rush to submit permits before the expiration of the favored 421-a tax program — has quickly receded back to an untenable status quo. This is despite the need for more than 560k new homes by 2030, on top of our existing shortage.

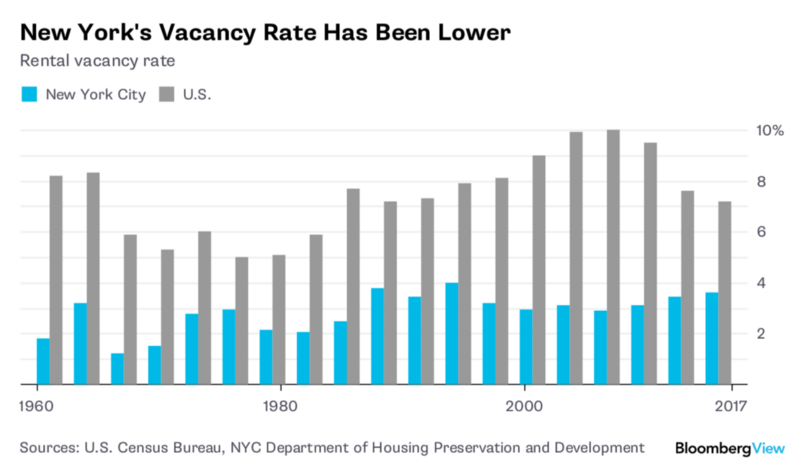

Economists have long known of the inverse relationship between a city’s vacancy rate, and the cost of housing. The lower the vacancy rate, the higher the cost of housing. Vice versa. Any reasonable city should be doing its best to increase the prevailing vacancy rate to take pricing pressure off of existing renters, and remove bottlenecks for those looking for housing (that is, if you want to avoid the 100 person lines for small, expensive units).

New York has not done this, to put it lightly. Under state law, when vacancy falls below 5%, a housing emergency can be declared. Since the city’s Housing and Vacancy Survey was first conducted in 1965, the vacancy rate has never been higher than 5 percent. New York City has been in a housing emergency for more than half of a century. Uncoincidentally, the city has failed to reach its peak of permits issued for new housing, which was prior to 1965.

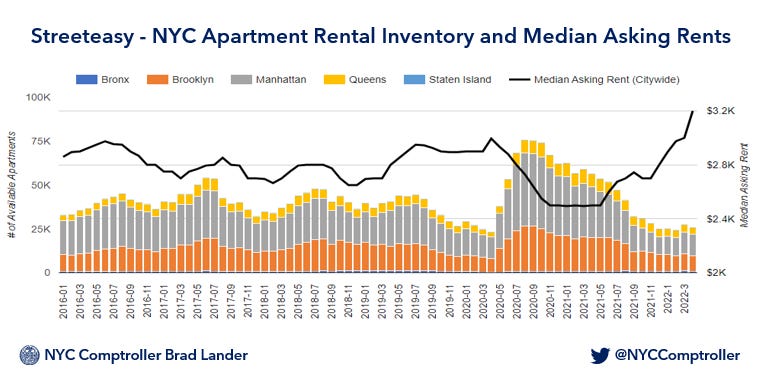

This has grown ever more acute in the last 6 months. The chart below from Comptroller Brad Lander’s office puts it into stark realty. As the number of units available decreases, the median rent increases. This should dispel the myth that a a few unsold units in luxury towers could solve our housing crisis, to say nothing of the fact that land use economics wouldn’t permit large rental buildings from being built in those locations anyway, as the rents could not support the land & construction costs on the small, narrow sites.

Well intentioned policy isn’t meeting reality

Legislators and public officials have worked hard for solutions in response to rising rents. In June of 2019, the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act was passed with the intention of providing stability to an expensive housing market through bolstering tenant’s rights generally, and expanding protections for marginalized renters specifically. While well-intentioned, it has had some serious, and not unanticipated consequences.

We’ll start with the positives. HSTPA has certainly helped tenants in a few ways; it has restricted evictions of dubious merit, reformed the notoriously suspect practice surrounding security deposits, and has granted greater deference to renters in legislative proceedings. In general, it has provided more leverage to tenants, and stability to long term renters. These are good things that should be stepping stones to more progressive housing policy.

However, a lack of understanding of land use economics has undone much of the good intended by these laws. This is because housing crises are issues of supply, not demand. On their own, tenant protections — demand side solutions — do little to solve a housing crisis. In fact, they can exaggerate already extreme conditions if they’re not married with more supply.

In economic terms, housing operates in a competitive market. It’s responsive to supply and demand. If demand for a good is high, and supply is low, the cost for that good will increase as many people bid up the price for a single scarce good. The jobs-to-homes imbalance over the last decade in New York is a good example of this. The only way to reach an equilibrium in pricing is to create more supply to satisfy demand. This is true whether the product is housing, soda, cars, or cell phones. To continue the jobs-to-homes example, the only way to sustainably reduce pricing pressure for the 3.25 people who received new jobs is to create 3.25 apartments, not enact protections so that the 1 person who lived there before can remain, and the 3.25 new folks have to go find somewhere else to live. They will simply find somewhere else to live that isn’t restricted, bidding up those few market rate apartments available, while those of lower means struggle significantly more.

This is precisely what’s happened. HSTPA has made rent regulation permanent for all buildings of 6 units or more built before 1974. Apartments are stabilized for structures built before 1947, so long as the tenant moved in after 1971. This means that nearly half of the city’s 2.18 million rental units are stabilized.

Rent stabilization might well be good for those who live in, or are able to access, a stabilized unit, but devastating for those who cannot. With the median rent of a stabilized apartment being $1,400, less than half of the $3,200 median average city wide, and almost a third of the median rent in Manhattan, why would one leave? And in the rare event that one does, those apartments won’t see the free market upon lease expiration, but instead will operate in a grey market where the friends or families of connected parties will get first access to those units, effectively pulling them off the visible rental market entirely. This is a point Stephen Smith has made convincingly on Twitter.

Not only are we not building enough, but worse, we’ve effectively taken half of the homes off of the market. This is why when one goes on StreetEasy to look for somewhere new to live, as most New Yorkers do, there seems to be nothing on the market. That’s because there isn’t. With low vacancy rates, half of the city’s apartments stabilized, and the other half being fiercely contested over, there aren’t many apartments to go around. People are fighting over less of an already scarce good, causing rental prices to skyrocket well beyond what one might reasonably expect if the market were allowed to respond to its supply-demand imbalance.

This has made prices dramatically more expensive for everyone else, as they (rightfully) perceive they must spend more to secure an elusive place to live. Stabilizing more than a million homes without providing enough new ones has been gasoline on the fire of a half-century long housing crisis, accelerated by an influx of demand to move into the city post-Covid. This does a tremendous injustice to those who don’t have protections in the stabilized market, to say nothing of spurning those who would like to live here but can’t justify fighting over a $4,000, 400 square foot box against 100 would-be residents, all desperate to move to New York.

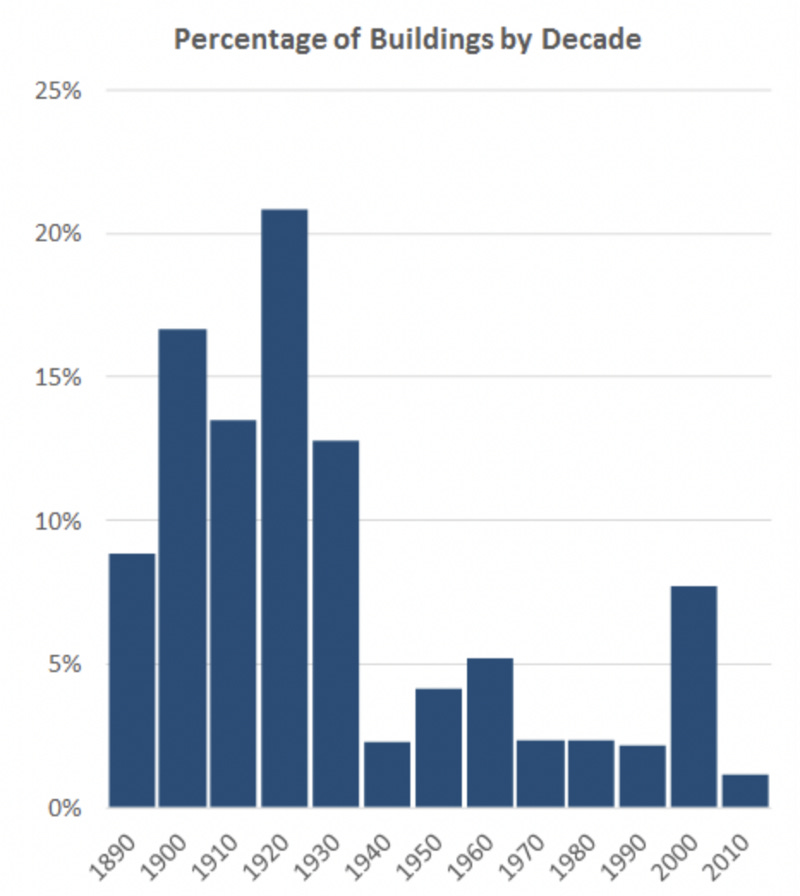

What’s worse, as any renter in New York will tell you, the issues aren’t just that the prices are more expensive, but that the quality is very poor as well. New Yorkers are used to paying more for getting less. But now, they’re getting significantly less. As the city hasn’t built a sufficient amount of housing in the last half century, most of its housing supply is old. Very old. Indeed, the median age of a residential building in New York is 90 years old. These buildings require serious capital needs in order to stay standing upright.

Regrettably, HSTPA severely limited the feasibility of making what are in many cases critical improvements. The bill capped the dollar amount of renovations that any unit can have over a 15 year period to just $15,000, and limited the amount of rent that could be charged to compensate for larger, major capital improvements, to just 2% a year. Far from protecting protect tenants from high price increases attributable to what have been described as non-essential, cosmetic interventions, this policy ensures that no improvements will be made to a given unit so long as the legislation is on the books.

Here’s why; If a landlord cannot get paid back for an investment made into a building, be it a new air conditioning system, a broken stairwell, or just outdated appliances, they simply won’t do it. This isn’t a capitalist imperative, or a signal of moral destitution, as the condition is the same in a a free market, rent stabilized, or Public Housing unit. Ultimately, everything costs money, whether one is in a capitalist or democratic socialist regime. One cannot simply get something for nothing, as the electrician, the plumber, the mason, the maintenance tech, and anyone who works in the building trades — predominantly blue collar, working class folks — needs to get paid. While the funding sources may be different — landlords in the free market have to pay a return on capital to private limited parters, and Public/Affordable landlords must have sufficient tax dollars that are not infinite — the funding uses are not.

If a landlord cannot recover more than 2% annually for major renovations, their funding sources will become expired far quicker than rents or capital appreciation can replenish them. This is partly why NYCHA, New York’s Public Housing Authority, needs $40 billion just to bring its 177,000 units up to habitable standards, like removing mold ($15B) lead ($1.6B), and performing other basic repairs ($2.2B). Hundreds of thousands of people are faced with unacceptable, and unsafe conditions. Public Housing residents shouldn’t see steep increases in rent, but if there aren’t shrewd provisions for the unavoidable capital needs of a building, which many are only too happy to fail to acknowledge, real people will face dire consequences.

It’s in this vein that it’s a bit strange that there was such an uproar about rents being raised on stabilized units. They weren’t hiked 20% annually, but 3.25%. That’s less than half of the annualized inflation rate for 2022 . This isn’t enough to compensate for increases in taxes and operational services year over year, to say nothing of larger capital needs. Indeed, there have already been significantly lower filings for improvements in the two years since the passage of HSTPA. This spells existential danger for the city’s housing stock.

We could very well see a crisis along the lines of NYCHA’s deteriorating supply for the million plus rent stabilized units, where it won’t be economically possible — unless with extraordinary subsidy — to provide apartments protections from mold, pest infestations, or basic heat in the winter. It is not possible to maintain the housing supply in a good condition with these limitations. Well intentioned policy will not result in the most desirable conditions if second and third order consequences are not considered.

It won’t get better until things change

New York will remain a very desirable place to live, unless and until the city stops responding to its most pressing needs, as others have succumb to.

New York real estate is not expensive because there’s a bubble, not because the greed of landlords is so severe (net income margins for most landlords ranges in the 3–5% range), and not because of a deluge of private equity investors (I won’t link to the endless pieces written on this topic, as there’s little empirical data to support the scapegoatery). It’s expensive because that’s how a competitive market responds to a disequilibrium between supply and demand.

If you find yourself wanting to blame landlords or developers or super tall towers for expensive housing, I’d urge you to direct that ire towards your council members, public officials, and legislators who actually control the levers that impact the cost of housing. Developers are merely builders, nothing more, nothing less. They play within the rules that are set out for them, and if they’re not allowed to play in one area, they’ll move to the next. So much the worse for the city who has turned them away, as they cannot build on their own.

The solution is simple. Build more housing through reforming zoning codes & other building regulations. But more than that, the city must build its housing well, with good foundations, better transit accessibility, more pedestrian and bicyclist infrastructure, and partnerships with regional municipalities to ensure everyone is doing their fair share, whether you’re a wealthy neighborhood, or one that’s marginalized.

Public policy has gotten us into this mess, and threatens to make it worse. A vast and scandalous incompetency on behalf of the city to not effectively manage a simple market imperative has let the situation get out of control. But luckily for us, thoughtful policy that responds to the lived experiences of people on the ground can get us out of this mess, too. Nearly everything you see in a city can be drawn back via a straight line to some policy made at some time in the past— from high costs of housing, inequality, highways through neighborhoods, and even where one can go to the grocery store. It’s time to alter the trajectory of these policy lines in New York and elsewhere, and draw ourselves into a more affordable, more equitable, and better future.